(Left to right) Inés María Chapman Waugh, Beatriz Jhonson Urrutia Image and Salvador Valdés Mesa. Image made by the author with images from EcuRed.

On April 19, 2018, the Republic of Cuba swore in former university professor Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez as its new president and the 9th Congress of the National Assembly of People’s Power—the country’s supreme body of government power—elected a new Council of State. But the euphoria and uncertainty surrounding a supposed “Cuba without Castros” and related matters have eclipsed another major development: the presence of four Black leaders who will be part of the new government through 2023.

Black Cubans make 10% of the population but their representation in circles of power has been very limited, in spite of the ideals of the equality after the revolution.

Before Bermúdez, the previous Congress had two Black men in senior positions: First Vice President Juan Esteban Lazo Hernández and Salvador Valdés Mesa, President of the National Assembly. With the selection of Inés María Chapman Waugh and Beatriz Jhonson Urrutia as vice presidents, Cuba has, so to speak, “added more color” to the government.

Before I discuss the two women, I want to spend a minute on Valdés Mesa and Lazo Hernández.

Valdés, who previously held the positions of secretary of the Workers’ Central Union of Cuba, Minister of Labor and Social Security, and Secretary of Agricultural Workers, among others, is not from the generation of “los históricos” meaning those who led the 1959 Cuban Revolution, and who have usually ceded power only when they’re ousted or die. He is from the generation that followed, as is Lazo, who was elected President of the National Assembly in 2013 and will keep the position until 2023, when he will be 79.

Lazo has a long and varied trajectory in Cuban politics. He has been secretary of the Cuba Communist Party for the Matanzas, Santiago de Cuba, and Havana provinces, a member of the Cuban parliament since 1981, and Vice President of the Council of State since 1992. Lazo has also represented Cuba’s foreign affairs with countries in the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. He was elected President of the National Assembly of People’s Power on February 25, 2013.

A new crucible of scrutiny

The two new women vice presidents are by parliamentary standards—only about 13% of members are under 35.

Ines María Chapman Waugh, from Holguín, is an engineer. Currently president of the National Hydraulic Resources Institute, for Cubans she’s a household name. For some time now she’s been the face of the agency she heads, offering the public important information during hurricane season. She was a member of the National Assembly for the preceding Congress and has been a member of the Council of State since 2008. In 2011 she was elected to the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party.

Beatriz Jhonson Urrutia is also an engineer. In 2011 she was elected vice president of the Provincial Assembly of People’s Power in her native province of Santiago de Cuba. She became President of this body in 2016. In the 7th Congress round a decade ago she was elected to the Central Committee. She became a member of parliament in 2013.

Both Chapman Waugh and Jhonson Urrutia come from the grassroots and developed professional careers prior to or alongside their political ones. As Black women, they’ve had to work hard at getting their degrees and building their careers to this point. And these latest appointments don’t mean they have arrived. Now they enter another crucible, where they’ll be “tested” due to their blackness and subjected to racist scrutiny and the expectation that sooner or later they will undoubtedly mess up.

Silence is also racism

Why haven’t the Cuban and international press, and people in general, embraced and hailed these developments with enthusiasm? I find it suspicious, considering that in the current political scenario this is a bigger surprise than Díaz-Canel, whose appointment was expected. The media has now turned its attention to the first lady and other superficialities while continuing to ignore this key piece of news.

Making things invisible is one of the ways racism operates. At times silence says more than words ever could. What I think is at work here is a combination of fear of Blackness with the casual neo-racism of everyday life. This includes the official notion, in Cuba, that speaking of Blackness, racism, and racial discrimination divides the nation.

About this last point, I want to add that even among the most committed social and political activists and laypeople, the idea persists that considering racial issues in any way dilutes a vaguely defined “supreme goal”. It’s from this position that notions ranging from the term “Afro-Cuban” to whether there is structural racism in the country are challenged.

While it is fair to assume there’ll be no change to race-related policies, it’s worth pointing out that the arrival of these three Black legislators, especially the two women, speaks favorably of the drive towards inclusion. Or, at the very least, it hints that it has been taken into account in the highest spheres of power on the island.

We can assume that no one holding a seat in the National Assembly has an explicit anti-racism political agenda. As members of the Cuban Parliament, how could they? And I see this as evidence of racism, along with the particularities of the Cuban electoral system and the intricacies of how one becomes “political” in Cuba. This is a country where independent activism falls outside of legitimatized spaces of power—which creates the anomalous situation where people completely lacking in political interests or public recognition can sit, for five years, in the supreme branch of government.

Changing that would require convincing those in the corridors of power that racism is currently Cuba’s most urgent problem. It’s connected to many others, such as poverty. It limits the enjoyment of basic and universal rights such as access to university education.

The fear of tackling the issue is evident in the minimal impact that so many race-related publications, research and theses have had on Cuba’s decision-makers. I wonder what else is needed to prompt an open acknowledgement of this matter and everything it entails—and the ensuing public policy proposals to address racism.

Racial issues are not listed as topic/objective in any of the ten permanent working groups of the National Assembly of People’s Power. I can think of at least three that are relevant to the issue of race: the Commission for the Attention of Childhood, Youth, and Equal Rights for Women; the Commission on Economic Issues; and the Commission of Education, Culture, Science, Technology, and the Environment.

There’s no racism in Cuba, ¿de verdad?

If there’s a subject on which Cubans at opposite ends of the political spectrum agree, it’s racial discrimination. Both supporters and opponents of the Cuban government assert wholeheartedly that “in Cuba blacks and whites are the same.” For government supporters on and off the island, the situation looks good enough, including on this issue. For opponents everywhere, things in Cuba are so terrible and everyone is so equally oppressed that racial discrimination is unworthy of special attention. These dynamics hijack the discussion and keep us from moving forward. Among some in the exile community, Cuban-flavored racism has even superseded anti-government animosity.

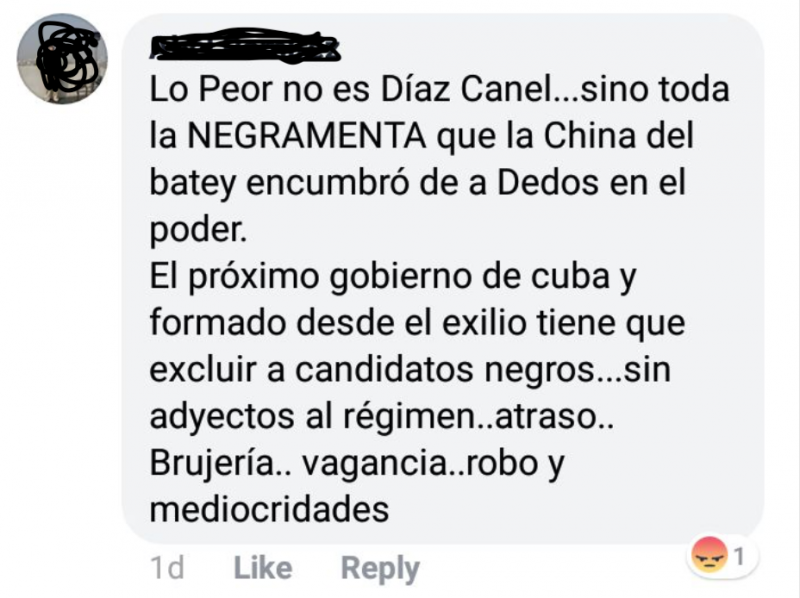

A screenshot from Facebook: “Diaz Canel is not the worst of it all. It’s the “N*****-load” left by [homophobic, racist, and xenophobic Cuban euphemism to refer to] Raúl Castro within inches of Power. The next Cuban government, and formed from exile, has to exclude Black candidates…no ties to the regime, witchcraft, laziness, theft, and mediocrities”

By now, we should have been implementing solutions, for example, to the problem of the overrepresentation of Black and mixed-race Cubans in the prison population. There should already be progress towards affirmative action on self-employment community projects.Nevertheless, the fact that there are now more senior politicians representing Black Cubans, even if imperfectly, fills me with optimism. I do not ask anything of our three Black VicePresidents that I wouldn’t ask of other legislators, but tackling racism and discrimination in Cuba requires the participation of all members of the society, within the spaces of power and privilege each of them occupies.

This article appeared originally on the blog Negra cubana tenía que ser.

19 total views, 1 views today