Local Communities in Mexico Show Ways to Fight Obesity

A farmer harvests amaranth in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. This grain, of which two of the varieties originated in Mexico, is part of the country’s traditional diet and can help boost nutrition among Mexicans, who have been affected by skyrocketing consumption of junk food. Credit: Courtesy of Bridge to Community Health

- Manuel Villegas is one of the peasant farmers who decided to start planting amaranth in Mexico, to complement their corn and bean crops and thus expand production for sale and self-consumption and, ultimately, contribute to improving the nutrition of their communities.

“Amaranth arrived in this part of the country in 2009, and some farmers were already growing it when I began to grow it in 2013. It’s growing, but slowly,” Villegas, who is coordinator of the non-governmental Amaranth Network in the Mixteca region, in the southern state of Oaxaca, told IPS.

This crop has produced benefits such as the organisation of farmers, processors and consumers, the obtaining of public funding, as well as improving the nutrition of both consumers and growers.

“We have made amaranth part of our daily diet. It improves the diet because of its nutritional qualities, combined with other high-protein seeds,” said Villegas, who lives in the rural area of the municipality of Tlaxiaco, with about 34,000 inhabitants.

The peasant farmers brought together by the network in their region plant some 40 hectares of amaranth, although the effects of climate change forced them to cut back production to 12 tons in 2017 and six this year, due to a drought affecting the area. To cover their self-consumption, they keep 10 percent of the annual harvest.

Native products such as amaranth, in addition to defending foods from the traditional Mexican diet, help to contain the advance of obesity, which has become an epidemic in this Latin American country of nearly 130 million people, with health, social and economic consequences.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) states in “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018,” published in August, that the prevalence of overweight among children under five fell from nine percent to 5.2 percent between 2012 and 2017. That means that the number of overweight children under that age fell from one million to 600,000.

On the other hand, the prevalence of obesity among the adult population (18 years and older) increased, from 26 percent to 28.4 percent. The number of obese adults went from 20.5 million to 24.3 million during the period.

The consequences of the phenomenon are also clear. One example is that mortality from diabetes type 2, the most common, climbed from 70.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in 2013 to 84.7 in 2016, according to an update of indicators published in May by several institutions, including the health ministry.

Another impact reported in the same study is that deaths from high blood pressure went up from 16 per 100,000 inhabitants to 18.5.

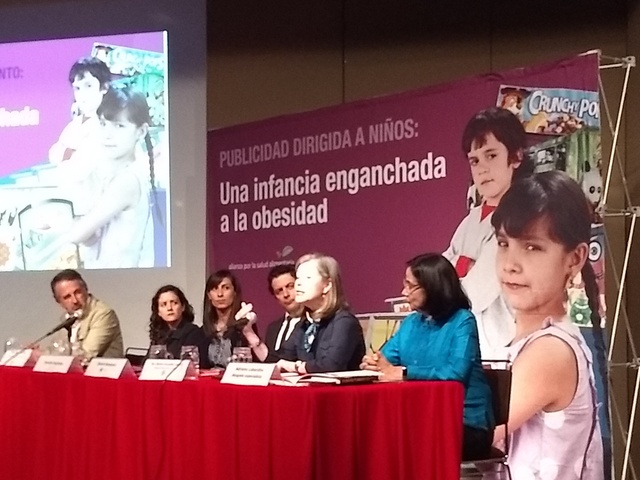

Members of the Alliance for Food Health, a collective of organisations and academics, called in Mexico for better regulation of advertising of junk food aimed at children and of food and beverage labelling, during the launch of the report “A childhood hooked on obesity” in Mexico City in August. Credit: Emilio Godoy/IPS

But the most eloquent and worrying data is that one in three children is obese or overweight, according to a reportpublished in August by the non-governmental Alliance for Food Health, a group of organisations and academics.

What lies behind

Specialists and activists agree that among the root causes of the phenomenon is the change in eating habits, where the traditional diet based on age-old products has gradually been replaced by junk food, high in sugar, salt, fats, artificial colorants and other ingredients, which is injected from childhood through exposure to poorly regulated advertising.

In 2013, the government established the National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Overweight, Obesity and Diabetes.

Its measures include the promotion of healthy habits, the creation of the Mexican Observatory on Non-Communicable Diseases (OMENT), the timely identification of people with risk factors, taxes on sugary beverages and the establishment of a voluntary seal of nutritional quality.

But the only progress made so far has been the creation of the observatory and the tax on soft drinks, since neither the regulation of food labels or advertising has come about.

In 2014, the state-run Federal Commission for Protection against Sanitary Risks created guidelines for front labeling of food and beverages, but did so without the participation of experts and civil society organisations and without complying with international World Health Organisation (WHO) standards.

For this reason, the non-governmental The Power of Consumers took legal action in 2015, and the following year a federal judge ruled that the measures violated consumers’ rights to health and information. The Supreme Court is now debating the future of labelling.

For Simón Barquera, an authority in nutrition research in the country, the solution is “complex” and requires “multiple actions.” “Society is responsible for attacking the causes of disease. The industry cannot interfere in public policy,” he said.

The latest National Health and Nutrition Survey found low proportions of regular consumption of most recommended food groups, such as vegetables, fruits and legumes, in all population groups. For example, 40 percent of the calories children ages one to five eat come from over-processed foods.

For Fiorella Espinosa, a researcher on dietary health at the civil association The Power of Consumers, the liberalisation of trade in Mexico since the 1990s, the lack of regulation of advertising and nutritional labels of products, the displacement of native foods and the prioritisation of extensive farming over traditional farming are factors that led to the crisis.

“There was an increase in availability and accessibility of overly-processed foods. The State failed to implement public prevention policies. Children live in an obesogenic environment (an environment that promotes gaining weight and is not conducive to weight loss). It’s a vulnerable group and companies take advantage of that to increase their sales,” she told IPS.

The 2017 Food Sustainability Index, produced by the Italian non-governmental Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition Foundation (BCFN), showed that this country, the second-largest in terms of population and economy in Latin America, has indicators reflecting a prevalence of over-eating, low physical activity and inadequate dietary patterns.

The index, which ranks France first, followed by Japan and Germany, analyses 34 nations with respect to sustainable agriculture, nutritional challenges and food loss and waste.

Obesity “is an epidemic that cannot be solved by nutrition education alone. It has structural determinants, such as the political environment, international trade, the environment and culture. It has social and economic barriers,” Simón Barquera, director of the Nutrition and Health Research Centre at the state-run National Institute of Public Health, told IPS.

Therefore, the Alliance for Food Health proposes a comprehensive strategy against overweight and obesity, which includes a law that incorporates increased taxes on unhealthy products, adequate labelling, better regulation of advertising and promotion of breastfeeding, among other measures.

The contribution of lifesaver crops such as amaranth

The organisations dedicated to the issue also highlight the recovery underway in communities in several states of traditional crops such as amaranth, a plant present in local food for 5,000 years and highly appreciated in the past because its grain contains twice the protein of corn and rice in addition to being rich in vitamins.

“We are looking for ways to generate changes at the community level in agriculture, food and family economy, focused on the cultivation of amaranth. We have realised that there has been a devaluation of the countryside and its role in adequate nutrition,” said Mauricio Villar, director of Social Economy for the non-governmental organisation Bridge to Nutritional Health.

Villar, also the coordinator of the Liaison Group for the Promotion of Amaranth in Mexico ,explained to IPS that “we are increasing our appreciation of peasant life and production, with impacts at different levels on nutrition,” to correct bad eating habits.

But according to Yatziri Zepeda, founder of the non-governmental AliMente Project, these local experiences, no matter how valuable their contribution, are limited in scope.

“These initiatives may generate changes at the local level and address some of the problems, but they are not sufficient to protect the right to health, among others. Obesity is not a matter of individual decisions, but of public policy. It is a political issue, there are very important corporate interests. It is multicausal and systemic,” she told IPS.

Print

Print